In November, Massachusetts passed Question 4, legalizing the recreational use of marijuana. Although legislators pushed up the implementation of the entire law, right now, there’s a lot of gray area local police departments such as Holliston, have to maneuver. The town is working to plan for potential implications.

On March 9th, at 7 p.m., the Holliston Police Department will hold a Community Engagement Forum in the Holliston Police Department Training Room, to inform the local community about the changes that will be going into effect.

“We’re going to take questions from the community on their concerns and some of the goals moving forward,” says Sgt. Matthew Waugh, of the Holliston PD. “We’re hoping some of the questions that come out will facilitate the dialogue.”

Within the police department, Sgt. Waugh has been the officer in charge of getting others up to speed on the legal ramifications of Question 4.

“We do monthly in-service trainings,” says Sgt. Waugh. “I’m actually the legal trainer, and in January, Keith and I taught Ashland, Holliston and Sherborn. The whole second half of the day we dedicated to changes on Question 4 passing,” he says. Not only did the two trainers discuss the legal interpretations of the law in terms of public safety and security, but they also conducted roundtable discussions between the three departments.

Some of the concerns officers brought up included OUI drugs.

“There’s a case currently in the Massachusetts courts right now, Commonwealth Vs. Gerhardt, an OUI drug case,” says Waugh. “With OUI alcohol, the courts have an accepted, standardized field sobriety test.” Road officers, he says, are trained in FST, or field sobriety tests. “So, with Gerhardt, the defense counsel is arguing that FST’s should not be admissible during court proceedings.” The court has yet to rule on the case, but the issue is one of concern among officers.

“With OUI alcohol, when we get the person back to the station, we have the Breathalyzer, to determine alcohol content in body, but we don’t have any device to determine a person’s intoxication from marijuana. An MIT professor developed an app you can hand to a person roadside, and they do a sobriety test on an iPad, but that’s not realistic for a street officer,” he says.

An officer can become trained as a Drug Recognition Expert, a two-week training, the actual training cost of which is picked up by the state, but that is prohibitive, because departments have to pay the cost of overtime and of travel, as officers need to train out of state to complete 12 roadside assessments of drivers who volunteer to do a narcotics assessment. The town of Franklin, for example, that has three trained DRE’s, has sent their officers to Colorado to complete this portion of the training.

A training that would be less expensive for Holliston to do is the two-hour Advanced Roadside Impairment Driving Enforcement (ARIDE) Training. Holliston has had just one officer out of Holliston’s 23 complete that training to date.

“There are three levels of training,” says Waugh. “Every officer gets Standard Field Sobriety Tests in the academy, and on the other side of the spectrum are DRE’s, trained to determine specific drugs. ARIDE training fills in that middle gap, where you could have more officers trained. It’s not necessarily a specific testing of a person, but (the officer) could provide legitimate testimony as to impairment of the driver.”

Sgt. Waugh says there is definitely a push to have more officers trained in Massachusetts, but Holliston had just one officer attend the most recent class, and he has only seen it offered twice.

“There’s definitely a hope that they do (provide training,” says Sgt. Waugh. Massachusetts, he says, is notoriously low in terms of the police training it provides. He points to the results of a Special Commission on Police Training study conducted for the state in 2010 that found that the state spent among the lowest ($187) per capita in training for its police officers. Some states, he says, are in the thousands.

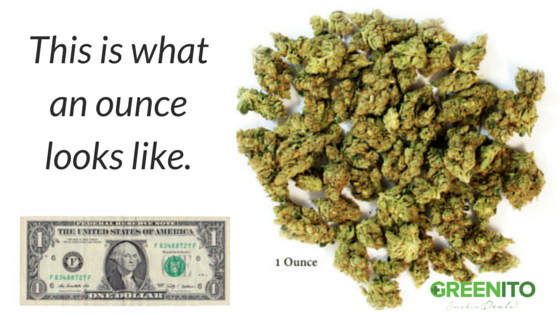

Until Holliston officers get the ARIDE training, however, they must grapple with the vagueness of the Question 4 law. In the open forums, some officers have brought up concerns of home growers offering back door deals, such as “giving” someone marijuana and then selling them a plastic bag for $100 or having customers pay them later. The law also states that if a person has less than two ounces of marijuana, that an officer should seize whatever is over one ounce, but officers have yet any way to determine that amount, unless they will carry scales.

“People are going to try to test the limits of the law,” says Waugh.

Another concern officers had related to home growing – six plants are allowable per adult, with a 12-plant maximum per house – concerns how much is produced.

“One plant can produce a pound,” says Waugh. “Theoretically, you can have bales of marijuana, just as long as it’s been grown through those 12 plants. That’s the interpretation we got from the Executive Office of Public Safety (EOPS). If our officers went into a house, and there were 100 pounds of marijuana, you would think that didn’t come from 12 plants, but you would have to test whether they are from the same strain. That goes way beyond the level you would expect an everyday police officer to determine.”

Waugh says the department intends to be open with the public at its forum Holliston, and its police officers, will need to acquaint itself with the ramifications of the new law when it rolls out in June of 2018, and hopefully, residents will come up with some valid concerns to address at the forum on March 9th.

“We’re a small department,” says Sgt. Waugh. “You’re not going to be successful unless you’re engaging the community.”

Open Discussion Will Address Concerns of Community Over Question 4 Changes

Issue Date:

March, 2017

Article Body: